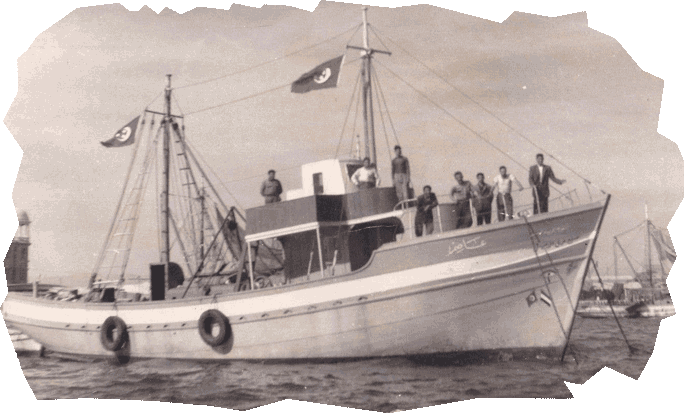

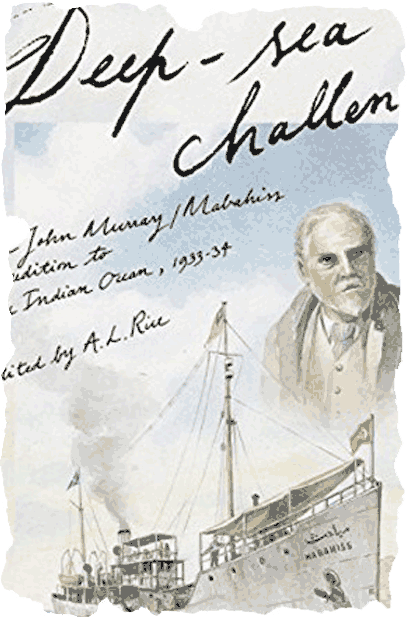

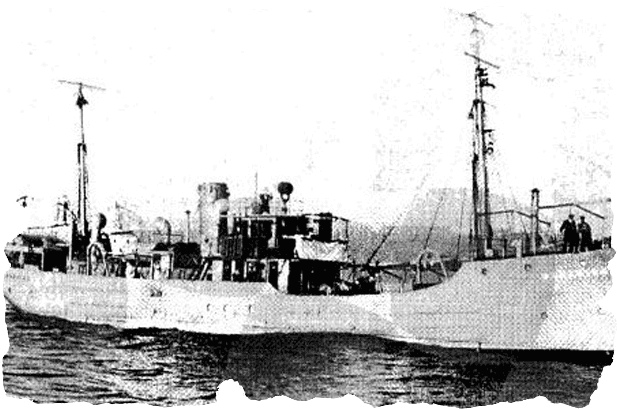

In the winter of 1934, Dr. Benjamin (Dean of the Faculty of Science at the Egyptian University) went to the officials of the Coast Guard and Fisheries Authority, carrying papers proposing that "Mabahiss" could go to a second exploratory journey, but it will be purely Egyptian, in a narrower range and for a shorter duration.

The success of its first voyage dominated their discussion, and they all got excited to do it again, but they thought about the cost. In the end, they allocated 2,500 Egyptian pounds for the project, but the development of Mabahiss will be postponed, because it will cost another 1,500 pounds.

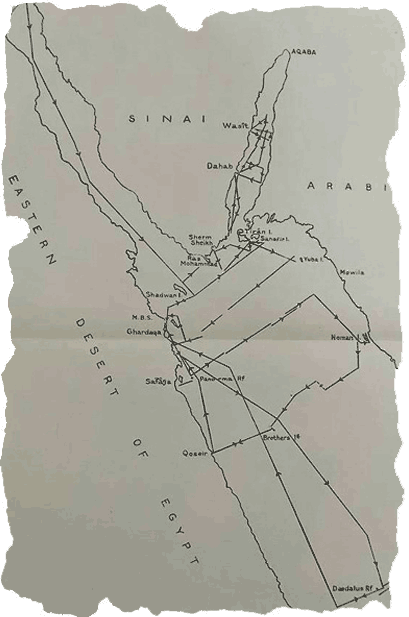

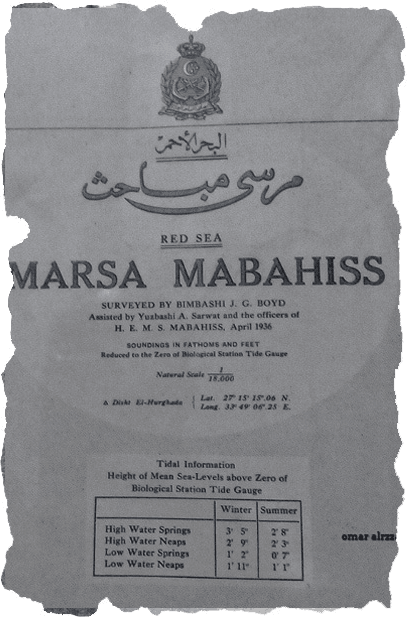

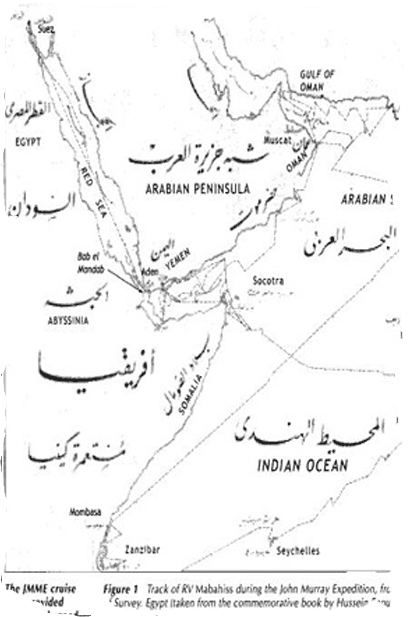

The Red Sea is the destination of Mabahiss this time, and it wasn’t new to it. It passed this sea through its previous voyage, but it didn’t expand it. On the afternoon of 18 December, It moved to Suez, then Port Said, and finally Hurghada.

On this trip, the team was all new; Except Abdel Fattah Mohamed, who became a professor of natural chemistry. And it may have been expected who will head the team. He's Dr. Crossland, the man who hosted Mabahiss and its crew in Hurghada on its first trip, and he was deeply impressed by it.